IFN Signaling Driven by Endogenous RNAs

Virus Infection Activates Interferon and Pattern Recognition Receptor Signaling

The interferon pathway is typically activated when cells become infected with a virus or other pathogen. Upon entry into host cells, virus-encoded RNA or DNA is often sensed by a family of cytoplasmic receptors called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). For example, cGAS senses cytoplasmic DNA while RIG-I senses cytoplasmic RNA. The activation of these PRRs leads to the production of the anti-viral cytokine interferon (IFN) and the induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs). This anti-viral response helps to rid the host of the virus.

Outline of PRR signaling that typically occurs after cells are infected with a virus. This results in interferon production and induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs).

Interferon-Stimulated Genes are Widely Expressed Across Human Cancers

Surprisingly, across nearly all human cancers examined, many patients have tumors that express ISGs even though it is unlikely that so many patients have tumors that are infected with a virus. These observations raise many questions.

What then is mimicking a virus infection in cancer cells and/or in the tumor microenvironment?

What are the consequences for cancer progression and response to therapy?

Are tumors that express these ISGs more aggressive or less aggressive?

How does the activation of anti-viral signaling impact the anti-tumor immune response and the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies?

Heatmap of interferon-stimulated genes expressed across many human cancers. Each column is a tumor and each row is an interferon-stimulated gene. Yellow indicates high expression and blue indicates low expression.

Cancer Cell Intrinsic Events and Signals from the Tumor Microenvironment Can Mimic Viral Infection

As cancers grow and evolve, many aberrant events occur that impact non-cancer cells, such as fibroblasts. One such event, which is a hallmark of cancer, is the invasion of malignant epithelial cells (carcinoma) through a basement membrane that normally separates these cells from fibroblasts. This results in the inappropriate interaction between epithelial cells, which are now cancer cells, and fibroblasts, which are now carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). In addition to these cancer cell extrinsic pathological events, cancer cells intrinsically are also abnormal. One example of an intrinsic defect is genomic instability. Thus, tumors are bombarded with signs and symptoms of damage. Could such intrinsic and/or extrinsic aberrations somehow mimic a virus to resemble danger/damage signals that occur with pathogen infection? If so, how does this generate an anti-viral response?

Examples of damage or danger signals in cancer that can activate PRR and interferon signaling. This include interaction between cancer cells and stromal cells, genomic instability of cancer cells, and other dysregulated processes in cancer that increase cellular stress.

Stromal Cells transfer Exosomes with Stromal RNA to Cancer Cells to Mimic Virus Infection

To understand how anti-viral responses are generated in the tumor microenvironment (TME), we first focused on the inappropriate interaction between cancer cells and fibroblasts. When cancer cells physically interact with fibroblasts, this can lead to the activation of these CAFs. One consequence of this activation is that stromal CAFs generate large amounts of exosomes, which are virus-sized vesicles that contain proteins and nucleic acids from the cells that generate them. Accordingly, when these exosomes are then taken up by cancer cells, this results in the transfer of RNA of CAF origin to the cancer cells. The cancer cells react to the CAF RNA in the exosomes as they would RNA from a virus, resulting in PRR activation in the cancer cells.

Depiction of events that occur when cancer cells interact with fibroblasts. The first step is activation of the fibroblasts. This is followed by exosome secretion, transfer to cancer cells, and activation of cancer cell PRRs by the stromal RNA.

RNA in exosomes can be “unshielded”, or No Longer protected by RNA binding proteins, which results in detection by Pattern Recognition Receptors

Although RNA from stromal cells can be transferred to cancer cells by exosomes, why does this result in activation of PRRs? Whatever this RNA is, isn’t it found in cancer cells anyways? It turns out that some types of RNA are stripped of its RNA binding proteins (RNPs) when the RNA is packaged into exosomes. One example is a non-coding RNA called RN7SL1. When RN7SL1 is in the cytoplasm of cells, it is nearly completely “shielded” by SRP9 and SRP14, two RNPs. This protein shielding essentially masks RN7SL1 from recognition by cytoplasmic PRRs. In contrast, when residing in exosomes, RN7SL1 appears nearly completely “unshielded” due to the absence of these RNPs in exosomes. It is this aberrant unshielded and unmasked version of RN7SL1 that is recognized by PRRs after transfer to cancer cells from fibroblasts, resulting in ISG induction and an anti-viral response similar to a virus infection.

Top plot compares RNA from cells to RNA from exosomes by examining both abundance (x-axis) and amount of unshielding (y-axis, where degree of unshielding is indicated by negative values). Bottom shows protein expression for SRP9 and SRP14 in cells and exosomes.

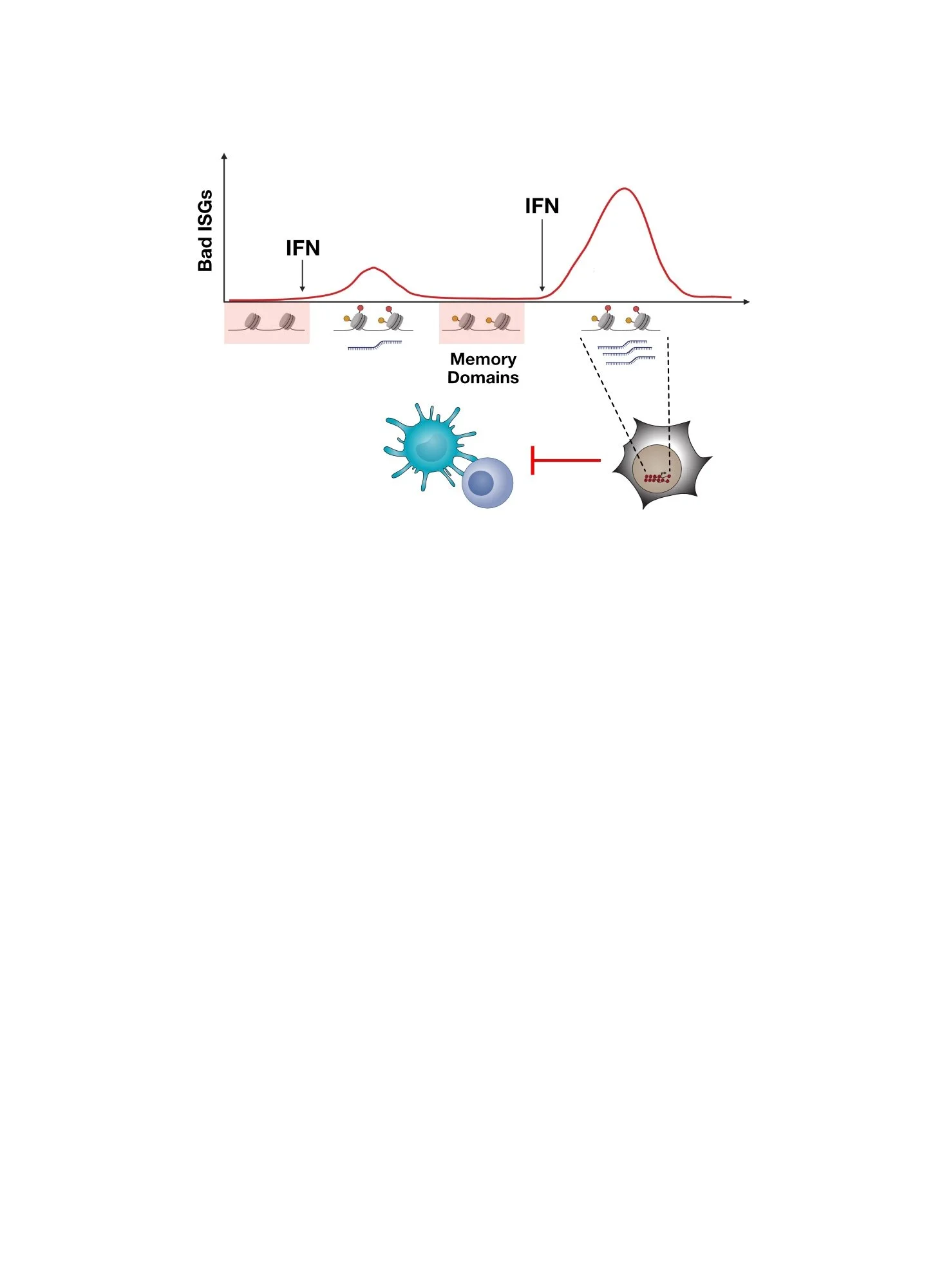

Consequences of Pattern Recognition Receptor Signaling in Cancer

What happens to cancer when PRRs are activated by RNAs like unshielded RN7SL1 or by other similar ligands generated or enriched by abnormal cancer-associated processes? Several lines of evidence indicates that many unfavorable consequences can ensue including metastasis and therapy resistance. In fact, blocking these signals can decrease metastasis and improve the efficacy of cancer therapies.

Besides cancer cells, what impact does chronic PRR and anti-viral signaling in cancer cells have on the immune cells in the tumor? Does it lead to a productive or a maladaptive immune response? Find out here. What happens if RN7SL1 is preferentially taken up by immune cells in the tumor rather than cancer cells? How can this be achieved? Find out here.

Summary of some of the consequences resulting from cancer cell PRR activation.

Watch a Video describing virus mimicry in the tumor microenvironment

Here is a Cell Video Abstract that summarizes some key findings.

Want to read more?

Visit our publications page to find the full references for our work.

Boelens et al, Cell 2014

Nabet et al, Cell 2017.

Here Are Some of the People That Led The Studies and Made It Happen!

Mirjam Boelens, former post-doc

Barzin Nabet, former grad student

Tony Wu, former research specialist

Bihui Melidosian (Xu), former grad student